I did not have a typical introduction to Singapore. I will tell this tale again, though my friends there have probably heard it enough times – it is my Southeast Asian version of Jude Law’s Shania Twain story from I Heart Huckabees. In this situation, Lee Wen is my Shania.

It begins with a rooster, the last sound I would’ve ever expected to awaken me in Singapore. It was 2015, and I had not yet discovered the criticality of earplugs. Late the night before, I had arrived in an Airbnb, dropped off by a taxi driver who insisted on cash. There was no hot water. And now I couldn’t sleep, because there was a rooster that wouldn’t fucking shut up.

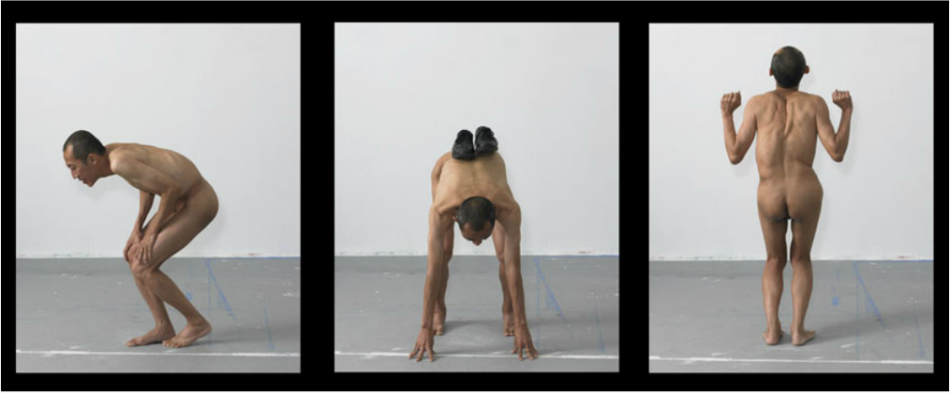

I soon learned that I was waking up to the Narnia of Singapore. My room was actually situated in the Independent Archive, and my roommate was none other than Lee Wen, who I soon learned to be an artist bigger than life, bigger than nation. Like the rooster, he was not what we from afar expect from Singapore – loud, obtrusive, walks around the henhouse like he owns the place. The first thing anyone would notice about him is his shape – his spine was arched forward like a rainbow, or a drain pipe. He walked in a way that could only be described as a “confident waddle” – like he had a chip on his shoulder, if the chip was the weight of a city-state. His hair was a messy gray and frayed. It swayed around like a wrung-out mop, especially when he pointed his lanky fingers upward to make a point. His eyes were a round pair of magic 8 balls, pupils glaring sharply like they were always seeing past a fog.

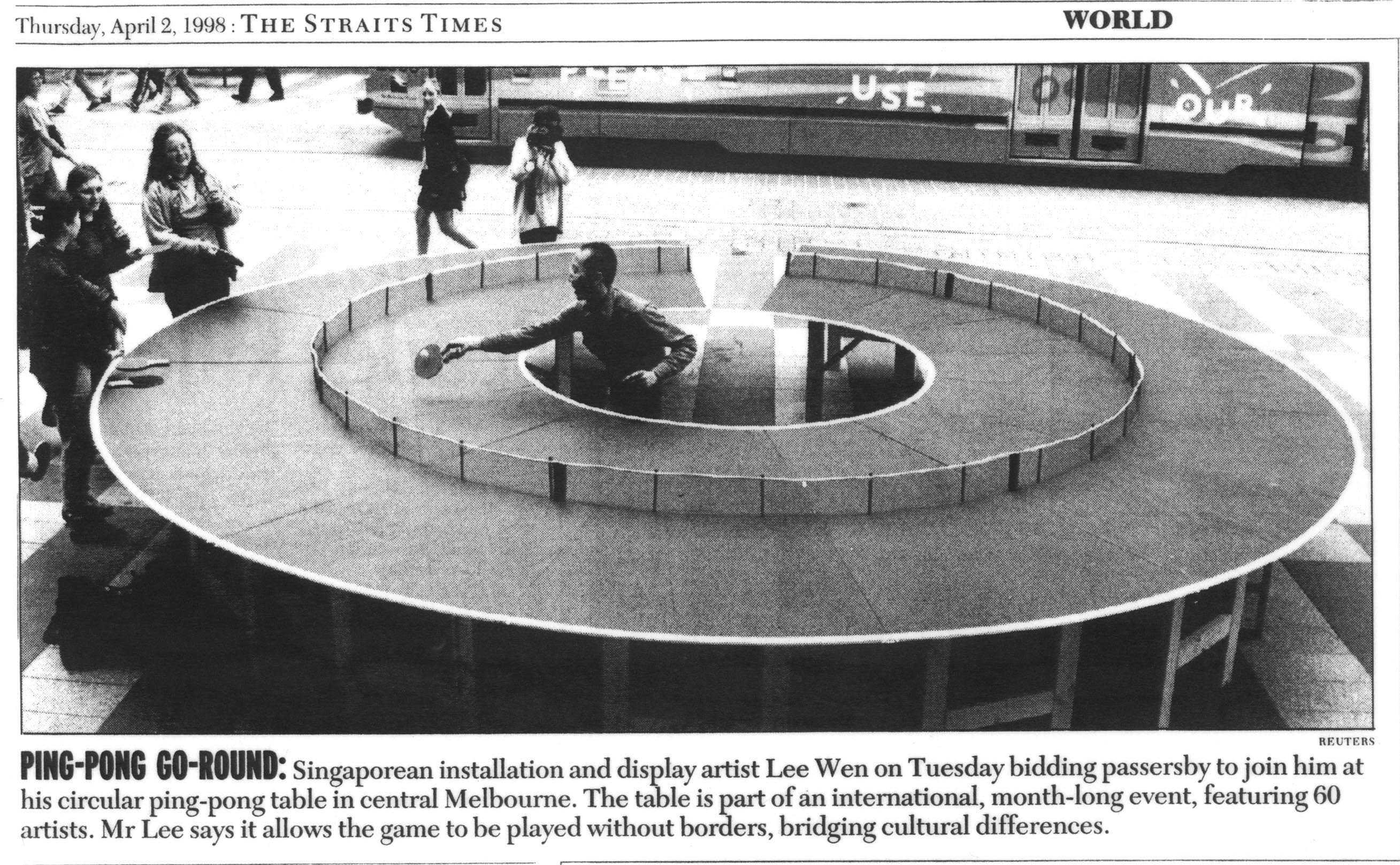

When most people think of Singapore, they think of the robotic architecture, Jetson-like amenities, the crazy-richness of it. But I think of this man. To even describe him as “dissident artist” is too limiting, perhaps even contradictory. He brought artists together, offered a template for vision that looked beyond material or mechanical aspiration. Singapore is the kind of place where you see so much crazy shit that normality begins to seem like a resistance, and Lee Wen resisted. In a document I found in my phone called Things Lee Wen Told Me, I was disappointed to find only the words “Radical shit vs radical chic” (I’m a horrible note-taker) But it unlocks so much of what I learned from him not only about Singapore, but what how the world steers the direction of change, for better or worse. How he had become accustomed to receiving runner-up awards, because his brand of commentary was too noticeable for a country so polite to simply shut down – better to give artists like him a cookie and then move the spotlight to someone more amenable. At some point I also recall him letting out a loud, long, rupturing fart while talking, and nobody else batting an eye even though it was impossible for anyone to have not noticed it. He just commanded that kind of respect.

The other line I took down, “Can’t balance with 1 foot on 2 boats,” is something that four years later I can hardly recall its meaning, but it does remind me of how he envisioned leaving Singapore one day, even though the way he said it wasn’t so convincing. He spoke so freely of his decaying health and the limitations of his mortality, a nihilism that was sharper than what he seemed willing to project onto Singapore.

Lee Wen died today. I learned about it over a text, while preparing for a project slated to open in Singapore the end of his year. The last few times I visited, he was too sick to be seen, or maybe it’s that I was too busy, or too distracted. Of course I entertained the idea of Lee being well enough to see the show, even though I knew chances were slim. But every moment I spend there is colored by the perspective he gifted me when I entered the country through his door. I think of him especially when I’m with Gerald, the artist who he lived with at the time, and who was responsible for setting up that fateful housing post that brought us all together. I remember sitting with him as he made his declarations, Gerald at the side, surely hearing whatever story was being uttered for the nth time. But some stories you just never get tired of hearing. Some stories should never stop being told.